People Feared the Japan Bomb Dropping So They Wouldnt Do It Again

When photographer Haruka Sakaguchi first tried to connect with survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, her common cold calls and emails went unanswered. Then, in 2017, the Brooklyn-based artist decided to visit Japan herself in hopes of coming together someone who knew a hibakusha—the Japanese give-and-take for those affected past the August 1945 attacks.

"I sat at the Nagasaki Peace Park for hours trying to differentiate between tourists and locals who were visiting to pray for a loved one—they often wore juzu, or prayer beads," says Sakaguchi, who immigrated to the U.Due south. from Japan every bit an infant in the 1990s. After five hours of people watching, she struck up a conversation with the girl of a survivor, who agreed to introduce her to 8 hibakusha.

Elizabeth Chappell, an oral historian at the Open University in the United Kingdom, encountered like difficulties after setting out to itemize atomic bomb survivors' testimony. "When you lot take a silenced group like that, they take a very internal civilization," she explains. "They're very protective of their stories. I was told I wouldn't go interviews."

Survivors' reluctance to talk over their experiences stems in big office from the stigma surrounding Japan'due south hibakusha customs. Due to a limited understanding of radiation poisoning'south long-term effects, many Japanese avoided (or outright abused) those affected out of fearfulness that their ailments were contagious. This misconception, coupled with a widespread unwillingness to revisit the bombings and Japan'southward subsequent surrender, led near hibakusha to proceed their trauma to themselves. But in the past decade or so, documentary efforts like Sakaguchi's 1945 Project and Chappell's The Last Survivors of Hiroshima accept get increasingly common—a attestation to both survivors' willingness to defy the long-continuing civilisation of silence and the pressing need to preserve these stories equally hibakusha's numbers dwindle.

When planning for the state of war in the Pacific's next phase, the U.S. invasion of mainland Nippon, the Truman administration estimated that American casualties would be between 1.7 and 4 million, while Japanese casualties could number upward to ten million. Per the National WWII Museum, U.S. intelligence officers warned that "there are no civilians in Japan," as the majestic government had strategically made newly mobilized combatants' attire indistinguishable from civilians. They also predicted that Japanese soldiers and civilians alike would choose to fight to the expiry rather than surrender.

Throughout World War II, the Japanese code of bushido, or "way of the warrior," guided much of Emperor Hirohito's strategy. With its deportment in China, the Philippines, the surprise set on on Pearl Harbor and elsewhere in Asia, the Imperial Japanese ground forces waged a barbarous, indiscriminate campaign confronting enemy combatants, civilians and prisoners of war. Prizing sacrifice, patriotism and loyalty in a higher place all else, the bushido mindset led Japanese soldiers to view their lives as expendable in service of the emperor and consider suicide more honorable than yielding to the enemy. Later in the war, equally American troops advanced on the Japanese mainland, civilians indoctrinated to believe that U.S. soldiers would torture and kill those who surrendered too started engaging in mass suicides. The Battle of Okinawa was a specially bloody example of this practice, with Japanese soldiers fifty-fifty distributing hand grenades to civilians caught in the crossfire.

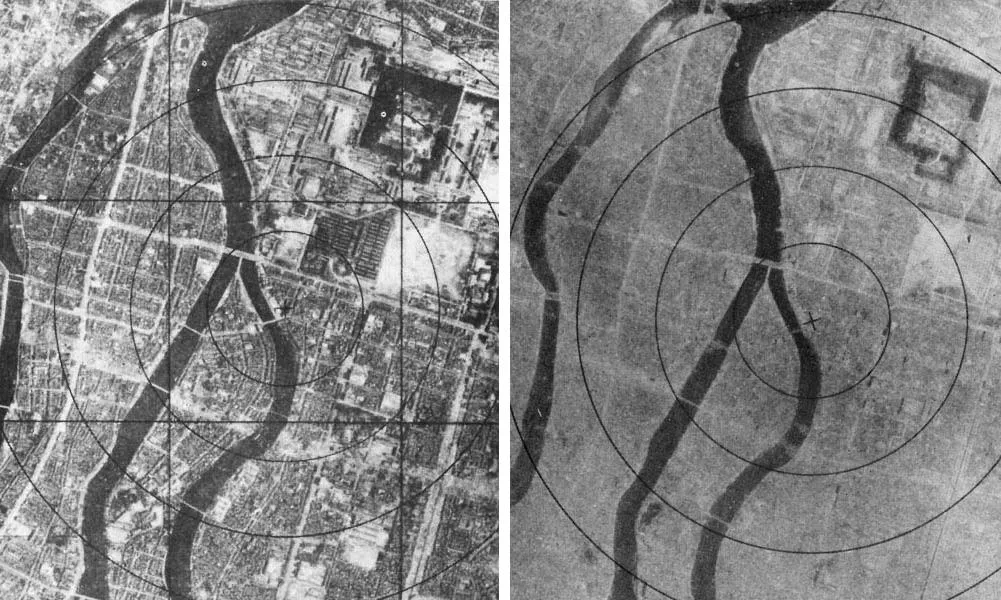

The accuracy of the U.Southward. government'south projections, and the question of whether Emperor Hirohito would have surrendered without the use of atomic weapons, is the subject of great historical debate. But the facts remain: When the bombing of Hiroshima failed to produce Japan'due south immediate give up, the U.Southward. moved frontwards with plans to drop a second diminutive bomb on Nagasaki. That same week, the Soviet Union officially declared war on Japan after years of adhering to a 1941 neutrality pact.

In total, the August 6 and 9 bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, killed more than than 200,000 people. 6 days after the second attack, Hirohito appear Japan's unconditional surrender. The American occupation of Japan, which fix out to demilitarize the land and transform it into a democracy, began soon after.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/07/cb078810-daa2-4478-9690-127034169ff7/gettyimages-92424064.jpg)

An estimated 650,000 people survived the atomic blasts, merely to detect their post-war lives marred by health issues and marginalization. Hibakusha received petty official help from the temporary occupying regime, every bit American scientists' understanding of radiation's furnishings was merely "marginally better" than that of the Japanese, according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation. In September 1945, the New York Times reported that the number of Japanese people who'd died of radiation "was very small."

Survivors faced numerous forms of discrimination. Survivor Shosho Kawamoto, for instance, proposed to his girlfriend more than a decade after the bombing, but her father forbade the marriage out of fearfulness that their children would bear the brunt of his radiation exposure. Heartbroken, Kawamoto vowed to remain single for the residual of his life.

"Widespread fears that hibakusha are physically or psychologically impaired and that their children might inherit genetic defects stigmatize starting time- and 2d-generation hibakusha to this day, especially female survivors," Sakaguchi says. (Scientists who monitored most all pregnancies in Hiroshima and Nagasaki between 1948 and 1954 found no "statistically significant" increment in nascence defects.)

Sakaguchi as well cites accounts of workplace bigotry: Women with visible scars were told to stay home and avoid "front-facing piece of work," while those issued pink booklets identifying them as hibakusha—and indicating their eligibility for healthcare subsidies—were ofttimes refused work due to fears of future health complications. Many hibakusha interviewed for the 1945 Project avoided obtaining this paperwork until their children were "gainfully employed [and] married or they themselves became very sick" in order to protect their loved ones from being ostracized.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/20/7120c1c3-ff25-47d6-bb4b-bd47af3dae3b/gettyimages-1035636670.jpg)

Peradventure the most jarring aspect of hibakusha's experiences was the lack of recognition afforded to survivors. Equally Chappell explains, far from reversing the empire'south decades-long policy of strict censorship, U.S. officials in charge of the postwar occupation continued to wield control of the printing, even limiting use of the Japanese discussion for atomic bomb: genbaku. After the Americans left in 1952, Nippon's government farther discounted hibakusha, perpetuating what the historian deems "global commonage amnesia." Fifty-fifty the 1957 passage of legislation providing benefits for hibakusha failed to spark meaningful discussion—and understanding—of survivors' plight.

Writing in 2018, Chappell added, "[T]he hibakusha were the unwelcome reminder of an unknown, unclassifiable upshot, something so unimaginable society tried to ignore it."

More than recently, crumbling hibakusha have grown more song about their wartime experiences. They share their stories in hopes of helping the next "generations imagine a different kind of futurity," according to Chappell, and to plead for nuclear disarmament, says Sakaguchi. Many organizations dedicated to preserving survivors' testimony—the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and the Hiroshima Peace Civilization Foundation, among others—were actually founded by hibakusha: "They had to be the outset researchers, [and] they had to exist their own researchers," Chappell notes.

Today, hibakusha nonetheless face widespread discrimination. Several individuals who agreed to participate in Sakaguchi's 1945 Project later withdrew, citing fears that friends and colleagues would encounter their portraits. Still, despite fear of retaliation, survivors continue to speak out. Below, observe nine such firsthand accounts of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, collected here to mark the 75th anniversary of the attacks.

This article contains graphic depictions of the atomic bombings' aftermath. The survivor quotes chosen from interviews with Sakaguchi were spoken in Japanese and translated by the photographer.

Taeko Teramae

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/1c/a61ce6ab-f43c-4f7d-b470-a5186b545164/harukasakaguchi_1945_042.jpg)

Hiroshima survivor Taeko Teramae didn't realize the full extent of her injuries until her younger brothers started making fun of her appearance. Confused, the 15-year-erstwhile asked her parents for a mirror—a request they denied, leading her to surreptitiously runway i downwardly on a day they'd left the house.

"I was so surprised I found my left eye looked just like a pomegranate, and I also found cuts on my right eye and on my olfactory organ and on my lower jaw," she recalled. "It was horrible. I was very shocked to find myself looking like a monster."

On the mean solar day of the bombing, Teramae was ane of thousands of students mobilized to help make full Hiroshima's wartime labor shortages. Assigned to the city'southward Phone Bureau, she was on the building's second floor when she heard a "tremendous dissonance." The walls collapsed, momentarily blanketing the workers in darkness. "I began to choke on the consequent smoke— poisonous gas, information technology seemed similar—and vomited uncontrollably," wrote Teramae in a 1985 article for Heiwa Bunka magazine.

Amid the din of cries for assistance, a unmarried voice called out: "We must endure this, like the proud scholars that we are!" It was Teramae'south homeroom teacher, Chiyoko Wakita, who was herself not much older than her students. Comforted past Wakita's words, the children gradually quieted down.

Teramae managed to escape by jumping out of a second-story window and climbing down a telephone pole. But when she tried to cross the Kyobashi River to safe, she found its only bridge in flames and the urban center she'd left behind "engulfed in a bounding main of fire." In one case again, Wakita came to her charge's rescue, accompanying her on the swim across the river and offering encouragement throughout the arduous journey. Afterwards dropping Teramae off at an evacuation centre, the young instructor returned to Hiroshima to assistance her other students. She died of her injuries on Baronial 30.

"[Wakita] saved my life, yet I was not able to tell her a simple 'thank you,'" Teramae subsequently said. "I deeply regret this, to this day."

Sachiko Matsuo

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/8b/838b784d-99fa-480b-9167-47d2981260a2/harukasakaguchi_1945_041.jpg)

Sometime before the bombing of Nagasaki, eleven-twelvemonth-sometime Sachiko Matsuo's begetter happened upon a leaflet dropped by American pilots to warn the city's residents of an imminent assault. Taking the message seriously, he constructed a makeshift cabin loftier up on a mountain overlooking Nagasaki and, in the days leading up to the scheduled bombing, implored his extended family to accept shelter at that place from morning until evening. But when August viii—the supposed day of the attack—passed without incident, Matsuo's mother and aunt told him they wanted to stay home.

Reflecting on the statement that followed in an interview with Sakaguchi, Matsuo said her begetter demanded that the pair return to the barracks, pointing out that the United States' time zone was one day behind Japan's. "When they opposed, he got very upset and stormed out to get to work," she added. Meanwhile, his remaining family unit members "changed our minds and decided to hibernate out in the barrack for i more solar day." The bomb struck but hours later. All those subconscious in the cabin survived the initial impact, albeit with a number of severe burns and lacerations.

"Afterward a while, we became worried about our house, and then I walked to a identify from where I would exist able to see the house, but at that place was something like a big cloud covering the whole urban center, and the deject was growing and climbing up toward united states," Matsuo explained in 2017. "I could see nix below. My grandmother started to cry, 'Everybody is dead. This is the end of the world.'"

Matsuo's father, who'd been stationed outside of an artillery factory with his ceremonious defense unit when the bomb struck, returned to the cabin that afternoon. He'd sustained several injuries, including wounds to the caput, hands and legs, and required a cane to walk. His eldest son, who'd also been out with a civil defense force unit, died in the boom. The family later spotted his corpse resting on a rooftop, but past the fourth dimension they returned to remember information technology, the trunk was gone.

In the weeks after the bombing, Matsuo's male parent began suffering from the effects of radiations. "He soon came down with diarrhea and a high fever," she told Sakaguchi. "His hair began to fall out and nighttime spots formed on his pare. My begetter passed away—suffering greatly—on August 28."

Norimitsu Tosu

Every morning, Norimitsu Tosu's female parent took him and his twin brother on a walk around their Hiroshima neighborhood. August vi was no different: The trio had merely returned from their daily walk, and the 3-year-olds were in the bathroom washing their easily. And then, the walls collapsed, trapping the brothers under a pile of debris. Their female parent, who'd briefly lost consciousness, awoke to the sound of her sons' cries. Bleeding "all over," Tosu told the National Catholic Reporter 's David E. DeCosse in 2016, she pulled them from the rubble and brought them to a relative'due south house.

Five of Tosu's seven firsthand family members survived the bombing. His father, temporarily jailed over an accusation of bribery, was shielded by the prison'due south strong walls, but 2 siblings—an older brother named Yoshihiro and a sister named Hiroko—died. The family was just able to learn of Yoshihiro'south fate: Co-ordinate to Tosu, "We didn't know what happened to [Hiroko], and we never located her torso. Nix. We didn't even know where exactly she was when the bomb exploded."

Given his historic period at the time of the assault, Tosu doesn't remember much of the actual aftermath. Simply as he explained to grandson Justin Hsieh in 2019, one memory stands out:

When we were evacuating, in that location were expressionless horses, dogs, animals and people everywhere. And the smells I remember. At that place was this terrible smell. It smelled like canned salmon. Then for a long time after that, I couldn't eat canned salmon considering the smell reminded me of that. It was sickening. And then more than than anything I saw or heard, information technology was the smell that I remember the nigh.

Yoshiro Yamawaki

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/01/76012a32-1b02-487e-9c61-38f268e3c31a/harukasakaguchi_1945_005.jpg)

The twenty-four hour period later on the U.S. dropped an diminutive flop on Nagasaki, eleven-year-old Yoshiro Yamawaki went out in search of his father, who had failed to return from a shift at the local power station. On the way to the factory, Yamawaki and two of his brothers saw unspeakable horrors, including corpses whose "skin would come up peeling off only similar that of an over-ripe peach, exposing the white fat underneath"; a young woman whose intestines dragged behind her in what the trio at first thought was a long white cloth belt; and a half-dozen- or 7-yr-old male child whose parasitic roundworms had come "shooting out" of his mouth post-mortem.

The boys soon arrived at the power station, which was situated near the bomb's hypocenter and had been reduced to little more than a pile of scorched metal. Spotting three men with shovels, they chosen out, "Our name is Yamawaki. Where is our father?" In response, one of the men pointed toward a demolished edifice across the street and merely said, "Your father is over in that location."

Joy quickly turned to anguish every bit the brothers spotted their begetter's corpse, "bloated and scorched just like all the others." After consulting with the older men, they realized that they'd need to either cremate his remains to bring domicile to their mother or bury his torso onsite. Unsure what else to do, they gathered smoldering pieces of woods and built a makeshift funeral pyre.

The men brash the brothers to come dorsum for their male parent's ashes the following day. Also overcome with emotion to remain, they agreed. But upon returning to the factory the following morning time, they found their begetter's half-cremated body abandoned and coated in ash.

"My brother looked at our begetter'due south body for a while longer, and and then said, 'Nosotros can't do annihilation more. We'll just take his skull dwelling and that volition be the end,'" Yamawaki recalled at age 75.

When the young boy went to recall the skull with a pair of tongs brought from home, however, "it crumbled apart like a plaster model and the half-burned brains came flowing out."

"Letting out a scream, my blood brother threw downwards the tongs, and darted away," said Yamawaki. "The ii of us ran after him. [These] were the circumstances under which nosotros forsook our father'southward body."

Sakaguchi, who photographed Yamawaki for the 1945 Project, offers another perspective on the incident, maxim, "Bated from the traumatic experience of having to cremate your own father, I was awestruck by Mr. Yamawaki and his brothers' persistence—at a young age, no less—to send their male parent off with quietude and nobility under such devastating circumstances."

Kikue Shiota

August 6 was "an unimaginably beautiful solar day" punctuated by a "blinding light that flashed as if a m magnesium bulbs had been turned on all at once," Hiroshima survivor Kikue Shiota later recalled. The blast trapped 21-twelvemonth-old Shiota and her sixteen-twelvemonth-old sis beneath the remains of their razed house, more than a mile from the bomb'south hypocenter.

Afterwards Shiota'southward begetter rescued his daughters from the rubble, they prepare out in search of their remaining family members. Burned bodies were scattered everywhere, making it incommunicable to walk without stepping on someone. The sisters saw a newborn babe still attached to its dead female parent'due south umbilical cord lying on the side of the road.

Every bit the pair walked the streets of Hiroshima, their x-yr-sometime brother conducted a similar search. When Shiota finally spotted him continuing amidst a oversupply of people, she was horrified: "All the skin on his face was peeling off and dangling," she said. "He was limping feebly, all the skin from his legs burned and dragging behind him similar a heap of rags."

The young boy survived his injuries. His 14-twelvemonth-one-time sister, Mitsue, did non. Though the family never recovered her trunk, they were forced to face the worst after finding a bit of Mitsue's school compatible burned into the asphalt.

"I idea my heart would surely stop because the very fabric I found was my sister's, Mitsue, my little sis," Shiota remembered. "'Mi-chan!' I called out to her. 'It must accept been terribly hot. The hurting must take been unbearable. Yous must take screamed for help.' … My tears falling, I searched for my sister in vain."

One month later on the bombing, the family lost another loved one: Shiota'southward mother, who had appeared to be in good health up until the day before her passing, died of acute leukemia caused by the blast's radioactive rays. She was cremated in a pit dug by a neighbor as her grief-stricken daughter looked on.

Akiko Takakura

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/37/cf37cb2f-fde2-4bcc-8446-412542c1fa70/ge14-06.jpg)

Decades later the bombing of Hiroshima, the epitome of a homo whose charred fingertips had been engulfed in bluish flames remained imprinted in Akiko Takakura'due south retentivity. "With those fingers, the homo had probably picked up his children and turned the pages of books," the and then-88-year-one-time told the Chugoku Shimbun in 2014. The vision so haunted Takakura that she immortalized it in a 1974 cartoon and recounted it to the many schoolchildren she spoke to as a survivor of the August vi attack. "More 50 years later, / I recall that blue flame, / and my heart virtually bursts / with sorrow," she wrote in a poem titled "To Children Who Don't Know the Atomic Flop."

Takakura was nineteen years erstwhile when the flop fell, detonating above a serenity street close to her workplace, the Hiroshima branch of the Sumitomo Bank. She lost consciousness after seeing a "white magnesium flash" but afterward awoke to the sound of a friend, Kimiko Usami, crying out for her female parent, according to testimony preserved by the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation. The pair managed to escape the building, which had partially shielded those inside with its reinforced concrete walls, and venture into the street. At that place, they encountered a "whirlpool of burn down" that burned everything it touched.

"It was just similar a living hell," Takakura recalled. "Afterward a while, it began to rain. The fire and the fume fabricated the states so thirsty and there was zero to drinkable. … People opened their mouths and turned their faces toward the sky [to] try to drink the rain, but it wasn't easy to catch the rain drops in our mouths. It was a black rain with big drops." (Kikue Shiota described the pelting equally "inky black and oily like coal tar.")

The fire eventually died down, enabling Takakura and Usami to navigate through streets littered with the "reddish-brown corpses of those who were killed instantly." Upon reaching a nearby drill ground, the young women settled in for the dark with only a sheet of corrugated tin can for warmth. On Baronial ten, Takakura's mother took her daughter, who had sustained more 100 lacerations all over her trunk, abode to begin the lengthy recovery process. Usami succumbed to her injuries less than a month later.

Hiroyasu Tagawa

In the spring of 1945, government-mandated evacuations led 12-yr-old Hiroyasu Tagawa and his sister to move in with their aunt, who lived a brusk distance abroad from Nagasaki, while his parents relocated to a neighborhood close to their workplace in the urban center center.

On the morning of August 9, Tagawa heard what he thought might be a B-29 bomber flying overhead. Curious, he rushed outside to accept a look. "Suddenly everything turned orange," Tagawa told Forbes' Jim Clash in 2018. "I quickly covered my eyes and ears and laid down on the ground. This was the position we skilful daily at schoolhouse for times like this. Soon dust and debris and pieces of drinking glass were flying everywhere. After that, silence."

All those living at the aunt'southward business firm survived the blast with pocket-size injuries. But later three days passed with no news of his parents, Tagawa decided to go to the city center and search for them. There, he found piles of corpses and people similarly looking for missing family unit members. "Using long bamboo sticks, they were turning over one corpse after the other as they floated downward the river," he recalled. "There was an eerie silence and an overwhelming stench."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/56/ab56d41e-0826-48db-98a4-def5c1e1d1b1/gettyimages-807123.jpg)

Tagawa'south female parent establish him start, calling out his name as he walked down the street. She and her husband had been staying in a shelter, too badly injured to brand the expedition back to their children. Mr. Tagawa was in particularly poor shape: A factory worker, he'd been handling dangerous chemicals when the bomb struck. Its impact sent the toxic materials flying, severely burning his anxiety.

Adamant to aid his ailing father, Tagawa recruited several neighbors to aid carry him to a temporary hospital, where doctors were forced to dismember with a carpenter's saw. His begetter died 3 days afterwards, leaving his grieving son uncertain of whether he'd done the right thing. "I wondered if I had done incorrect past taking him over at that place," Tagawa told the Japan Times' Noriyuki Suzuki in 2018. "Had I not brought him to accept the surgery, maybe he would've lived for a longer time. Those regrets felt like thorns in my heart."

More than tragedy was still to come: Shortly after Tagawa returned to his aunt'due south town to evangelize news of his father's expiry, he received discussion that his female parent—suffering from radiations poisoning—was now in critical condition. Bicycling dorsum to her bedside, he arrived just in time to say goodbye:

My aunt said, "Your mother nigh died last night, only she wanted to see you ane terminal fourth dimension. And then she gave it her best to live ane more solar day." My mother looked at me and whispered, "Hiro-chan, my honey child, grow upward fast, okay?" And with these words, she drew her last breath.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/24/50241346-e134-4e4a-b288-abb9bff64504/gettyimages-520831233.jpg)

Shoso Kawamoto

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/6a/8c6a0594-b99a-4abe-aac7-92a2f8c999dd/gettyimages-2637030.jpg)

Xi-year-old Shoso Kawamoto was ane of some 2,000 children evacuated from Hiroshima's city center ahead of the August half dozen bombing. As he told the Chugoku Shimbun in 2013, he'd been working in a field due north of the city alongside other immature evacuees when he noticed a white deject rise in the heaven higher up Hiroshima. That night, caretakers told the group of 6- to 11-year-olds that the metropolis center—where many of the children'southward families lived—had been obliterated.

Three days subsequently, Kawamoto'southward 16-year-old sis, Tokie, arrived to option him up. She arrived with sobering news: Their female parent and younger siblings had "died at home, embracing 1 another," and their father and an older sister were missing. Kawamoto never learned exactly what happened to them. (Co-ordinate to Elizabeth Chappell, who has interviewed Kawamoto extensively, his "samurai female parent and ... farmer begetter" came from different backgrounds and raised their children in a strict neo-Confucian household.)

After reuniting, the siblings moved into a ruined train station, where they witnessed the plight of other orphaned children. "[W]east did not have enough food to survive," Kawamoto subsequently explained to author Charles Pellegrino. "We were in a constant tug-of-war over food—sometimes only one dumpling. In the cease, the strong survived and the weak died ane afterward another." Most orphans died within months, wrote Chappell for the Conversation in 2019: Though local women tried to feed them, at that place simply weren't enough rations to go around.

Tokie died of an undiagnosed illness, likely leukemia, in February 1946. Post-obit her passing, a soy sauce factory owner took Kawamoto in, feeding and sheltering him in exchange for 12 years of labor. At the end of this period, the human rewarded his surrogate son with a house.

Tsutomu Yamaguchi

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/a7/4ea72902-6cf6-4838-81ae-b64c7b191fcd/gettyimages-85578931.jpg)

To date, the Japanese authorities has recognized only i survivor of both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings: naval engineer Tsutomu Yamaguchi, who died in 2010 at age 93. A longtime Nagasaki resident, he'd spent the summer of 1945 on temporary assignment in Hiroshima. Baronial 6 was set to exist his last day of piece of work before returning home to his wife and infant son.

That morning, the 29-twelvemonth-old was walking to the shipyard when a "great flash in the sky" rendered him unconscious. Upon waking upwardly, Yamaguchi told the Times' Richard Lloyd Parry, he saw "a huge mushroom-shaped pillar of fire rising upward high into the sky. It was similar a tornado, although it didn't motion, but it rose and spread out horizontally at the top. There was prismatic calorie-free, which was changing in a complicated rhythm, like the patterns of a kaleidoscope."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/52/0c52361d-782e-43b6-adb2-331998ea7d0f/gettyimages-568884791.jpg)

The blast ruptured Yamaguchi's eardrums and burned his face and forearms. But afterwards reuniting with two co-workers—Akira Iwanaga and Kuniyoshi Sato—the trio managed to think their belongings from a dormitory and start making their way to the train station. On the way, "Nosotros saw a mother with a baby on her dorsum," Yamaguchi recalled. "She looked every bit if she had lost her mind. The child on her back was dead and I don't know if she even realized."

Sato, who along with Iwanaga likewise survived both bombings, lost track of his friends on the train ride back to Nagasaki. He ended upwardly sitting across from a beau who spent the journeying clasping an awkwardly covered bundle on his lap. Finally, Sato asked what was in the package. The stranger responded, "I married a month ago, just my wife died yesterday. I want to take her home to her parents." Beneath the cloth, he revealed, rested his dearest's severed head.

Upon reaching Nagasaki, Yamaguchi visited a infirmary to receive treatment for his burns. Deeming himself fit to work, he reported for duty the side by side day and was in the middle of recounting the bombing when another blinding wink of calorie-free filled the room. "I thought the mushroom cloud had followed me from Hiroshima," he explained to the Independent'southward David McNeill in 2009.

Yamaguchi was relatively unhurt, and when he rushed to check on his wife and son, he found them in a similar state. Simply over the next several days, he started suffering from the effects of radiation poisoning: As Evan Andrews wrote for History.com in 2015, "His hair vicious out, the wounds on his arms turned gangrenous, and he began airsickness endlessly."

With time, Yamaguchi recovered and went on to live a normal life. He was, in fact, so good for you that he avoided speaking out near his experiences for fear of being "unfair to people who were actually sick," as his girl Toshiko told the Independent. In total, an estimated 165 people survived both bombings. Yamaguchi remains the only 1 to receive official recognition.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/nine-harrowing-eyewitness-accounts-bombings-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-180975480/

0 Response to "People Feared the Japan Bomb Dropping So They Wouldnt Do It Again"

Post a Comment